A Basic Introduction to Blockchain

TIP

Access all of my source documents here: https://u.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZK0s95ZKg9TWbEfy4m3HOWzeWsXmufVscUX

Overview

The provided text is an excerpt from "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System," the original white paper authored by Satoshi Nakamoto. This foundational document proposes a purely peer-to-peer system for online payments that eliminates the need for trusted financial institutions. The core problem it addresses is double-spending, which is solved using a distributed proof-of-work network that chronologically timestamps transactions and links them into an immutable chain, commonly known as the blockchain. The system relies on a majority of CPU power being controlled by honest nodes to ensure the integrity of the longest chain, which represents the agreed-upon history of transactions. The paper details the mechanisms for transactions, the role of the timestamp server, the network operation steps, and the financial incentives for network participants, concluding with a mathematical analysis of attacker probabilities.

How Bitcoin Works: A Simple Guide to Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash

Introduction: Why Bitcoin Was Created

Almost all commerce on the internet relies on financial institutions like banks to act as "trusted third parties" for processing electronic payments. While this system generally works, it has inherent weaknesses because it is built entirely on trust.

The core problems with this trust-based model include:

- Reversibility and Its Costs: Transactions are not truly final. Financial institutions must mediate disputes, which means payments can be reversed. This uncertainty for sellers is compounded by a broader cost: the loss of the ability to make non-reversible payments for non-reversible services, cutting off possibilities for certain kinds of commerce.

- Transaction Costs: The process of mediating disputes and managing trust increases transaction costs. These fees make small, casual transactions impractical.

- Trust and Fraud: Merchants must be wary of their customers, often collecting more personal information than necessary to protect themselves. Despite this, a certain amount of fraud is considered unavoidable.

Bitcoin was created to solve this problem. Its goal is to provide an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two parties to transact directly with each other without needing a trusted third party.

To understand how this system works without a bank, we first need to see how it defines a digital coin and ownership.

1. The Building Blocks of a Digital Coin

1.1. Defining Ownership with Digital Signatures

In Bitcoin, an electronic coin is defined as a "chain of digital signatures." The coin’s entire history of ownership is contained within it. An owner transfers the coin to the next person through the following process:

- The current owner creates a hash (a unique digital fingerprint) of the previous transaction and the public key of the next owner.

- The current owner then digitally signs this new hash with their private key.

- The owner adds the hash and the digital signature to the end of the coin.

A recipient can easily verify all the signatures in the chain to confirm the complete history of ownership and be sure the person sending the coin is the legitimate owner.

1.2. The Double-Spending Problem

This system creates a new challenge: how can a recipient be sure that the owner didn't already send that exact same coin to someone else? This is known as the double-spending problem.

The traditional solution is very different from Bitcoin's approach.

| Traditional Solution (The "Mint") | Bitcoin's Solution (The Network) |

|---|---|

| A trusted central authority (a "mint" or a bank) checks every transaction to see if a coin has already been spent. The entire system depends on this central party. | All transactions must be "publicly announced" to the entire network. All participants can then agree on a single, shared history of the order in which transactions were received. |

The key insight here is that to prevent double-spending without a central authority, the network needs a reliable way for everyone to agree on which transaction came first.

Bitcoin achieves this agreement using a public, timestamped ledger.

2. How Bitcoin Solves Double-Spending

2.1. The Public Ledger: A Timestamped Chain of Blocks

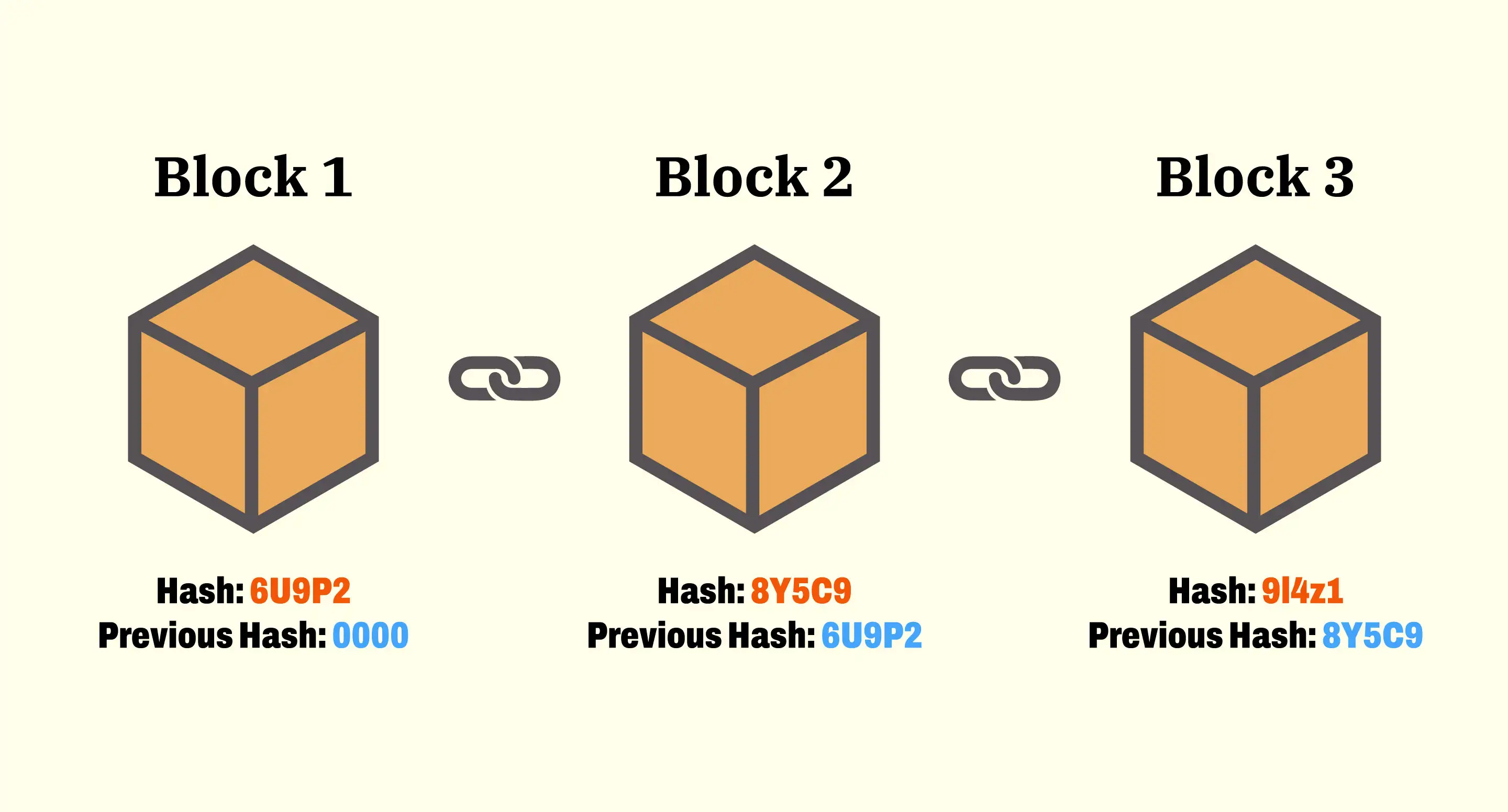

The solution begins with what is essentially a distributed "timestamp server." It works by bundling transactions into groups called "blocks" and then creating a permanent record of them.

This server takes a hash of a block of transactions and publicly records it. Critically, each new timestamped hash also includes the hash of the previous timestamp. This process creates a chain of blocks, where each block is cryptographically linked to the one before it.

The primary benefit of this chain is that it proves the data in a block existed at a specific time. As more blocks are added, each one reinforces the blocks that came before it, making the history extremely difficult to change.

2.2. Securing the Chain with Proof-of-Work

To implement this timestamp server in a decentralized, peer-to-peer network, Bitcoin uses a system called Proof-of-Work (PoW). This system requires participants (called "nodes") to expend significant computational effort (CPU power) to create a new block. To do so, they must find a value that, when hashed, produces a result that starts with a certain number of zero bits.

This computational work serves two crucial purposes:

- Security: Once the CPU effort is spent to create a valid block, that block cannot be changed without redoing all of that work plus the work for every single block that has been chained after it. An attacker would have to not only redo the work for a past block but also catch up to and surpass the work of the entire rest of the network.

- Voting: Proof-of-Work is essentially "one-CPU-one-vote." The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, because that is the chain with the greatest amount of proof-of-work effort invested in it.

The system remains secure as long as honest nodes, which are not cooperating to attack the network, control a majority of the CPU power. Their chain will always grow the fastest and outpace any attacker's chain.

Now that we understand the technical solution, let's see how the network of users puts it into practice.

3. The Bitcoin Network in Action

The process of running the network and creating this shared history involves a simple set of steps performed by all participating nodes.

- New transactions are broadcast to all nodes on the network.

- Each node collects these new transactions into a candidate block.

- Each node then works on finding the difficult proof-of-work for its block.

- When a node finds a valid proof-of-work, it broadcasts the completed block to all other nodes.

- Other nodes accept this new block only if all transactions within it are valid and have not already been spent.

- Nodes show their acceptance of the block by starting to work on the next block, using the hash of the newly accepted block as the foundation for the new one.

Nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one. If two nodes broadcast competing blocks at the same time, creating a temporary tie, other nodes will simply work on the one they received first. The tie is broken as soon as the next block is created, making one of the chains longer, at which point all nodes switch to working on that longer chain.

This brings up a logical question: why would people dedicate their computer power to perform this work for the network?

4. Why Participate? The Incentive System

The Bitcoin network has built-in incentives that encourage nodes to support it and, more importantly, to remain honest.

| Incentive Type | How It Works |

|---|---|

| New Coins (Block Reward) | The first transaction in every new block is a special one that creates a brand-new coin, which is awarded to the creator of that block. This is analogous to how gold miners expend resources (energy, equipment) to add new gold into circulation. |

| Transaction Fees | If a transaction's output value is less than its input value, the difference is a transaction fee. This fee is also collected by the creator of the block that includes the transaction. |

This incentive structure provides a crucial insight: it is more profitable for a powerful participant to "play by the rules" to generate new coins than it is to "undermine the system and the validity of his own wealth" by trying to attack it.

Beyond these core mechanics, the system has other important features related to privacy and usability.

5. Key Features of Bitcoin

5.1. The Privacy Model

While all transactions are public, privacy is maintained by keeping public keys anonymous. The public can see that an amount was sent from one address to another, but there is no information linking those addresses to real-world identities. This is similar to how a stock exchange makes the time and size of trades public, but not the identities of the buyers and sellers.

To further enhance privacy, it is recommended that users generate a new key pair for each transaction to prevent them from being linked to a common owner.

However, this privacy has limits. Some linking is unavoidable in transactions that combine multiple inputs, as this action reveals that all those inputs belonged to the same owner. If the owner of just one of those keys is ever identified, it could be possible to link them to their other transactions.

5.2. Simplified Payment Verification

It is possible to verify payments without having to run a "full network node," which requires storing the entire transaction history. A user only needs to keep a copy of the "block headers of the longest proof-of-work chain." By doing this, the user can confirm that a transaction has been accepted by the network and see subsequent blocks reinforcing that acceptance, all without needing the full blockchain data.

This convenience comes with a security trade-off. This verification method is reliable as long as honest nodes control the network, but it is more vulnerable if the network is overpowered by an attacker. A user relying on this simplified method could be fooled by an attacker’s fabricated transactions for as long as the attacker can continue to overpower the network, making it less secure than running a full network node for independent verification.

Conclusion: A New System for Electronic Transactions

Bitcoin is a system for electronic transactions that successfully removes the need to rely on trust. It achieves this by combining several key innovations into a robust and simple framework.

- Ownership: Coins are defined by a secure chain of digital signatures, providing strong control of ownership.

- Double-Spending Prevention: A peer-to-peer network uses Proof-of-Work to create a public, timestamped history of all transactions, making it impossible to spend the same coin twice.

- Security: This public history quickly becomes computationally impractical for an attacker to change, so long as honest nodes control the majority of the network's CPU power.

- Consensus: Nodes "vote with their CPU power" by accepting valid blocks and extending the chain, ensuring that the entire network agrees on a single version of history.

The Life of a Bitcoin Transaction: A Step-by-Step Journey

Welcome to the world of Bitcoin. At its heart, Bitcoin was designed to solve a fundamental problem of the digital age: how to exchange value online without needing to trust a middleman.

Think about how you use money. When you hand someone physical cash, the transaction is direct and final. There is no third party involved. However, commerce on the internet almost exclusively relies on financial institutions like banks to act as "trusted third parties" for online payments. While this system works, it has inherent weaknesses. Because these institutions must mediate disputes, truly non-reversible transactions aren't possible. This mediation adds costs, limits the potential for small, casual payments, and forces merchants to be wary of their customers to protect against fraud.

What was needed was a new approach: "an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust." Bitcoin was proposed as a solution, allowing any two parties to transact directly with each other and creating a public history that is computationally impractical to change, which in turn protects transactions from being reversed.

Let's follow the step-by-step journey of a single Bitcoin transaction to see how this system works.

1. Step 1: Crafting the Digital Handshake

At its core, a Bitcoin transaction is a secure, verifiable transfer of ownership. The system defines an "electronic coin" not as a single file, but as a chain of digital signatures.

Creating a transaction is like digitally signing over the ownership of that coin to the next person. The process involves the current owner signing a hash (a unique digital fingerprint) of the previous transaction and the public key of the new owner. This new signature is then added to the end of the coin, extending its chain of ownership. A recipient can easily verify all the previous signatures to confirm the chain of ownership is valid.

But this raises a critical question: how does the recipient know the sender didn't already send that exact same coin to someone else? This is known as the "double-spending" problem. In a traditional system, a central authority like a bank or "mint" would check for this. Bitcoin's solution is to replace that central authority with public transparency.

To solve this without a trusted party, transactions must be publicly announced, and the network needs a system for participants to agree on a single, shared history of the order in which transactions were received.

Now that the transaction has been created and signed, it must be announced to the world.

2. Step 2: Broadcasting the News

Immediately after a user creates and signs a transaction, the process begins when "New transactions are broadcast to all nodes" on the peer-to-peer network.

This broadcast is done on a "best effort basis" and doesn't need to reach every single computer in the world simultaneously. This is sufficient because, as the source text explains, "As long as they reach many nodes, they will get into a block before long." At this point, the transaction is public knowledge, waiting in a digital queue to be included in the official record.

This broadcast is the first step in getting the transaction officially recognized by the entire system.

3. Step 3: The Miner's To-Do List

As new transactions are broadcast across the network, certain nodes—often called miners—are constantly listening and gathering them. As one of the core steps of running the network, "Each node collects new transactions into a block."

Think of a miner gathering individual flakes of gold (transactions) with the goal of melting them down into a single, solid gold bar (a block). A block is simply a collection of recent, pending transactions. This means a transaction doesn't get processed instantly on its own; it sits with a batch of other transactions, waiting to be permanently recorded.

The block is now assembled, but it isn't yet official. An intense computational race is about to begin to determine which miner gets to add their block to the permanent record.

4. Step 4: The Proof-of-Work Puzzle

This step is the engine that secures the entire network. To add a block to the official chain, a node must first solve a difficult computational puzzle. This process is called Proof-of-Work.

- The Goal: Each node with a candidate block of transactions now works on "finding a difficult proof-of-work for its block."

- The Method: The process involves a brute-force search. A node takes all the data in its block and repeatedly hashes it, "incrementing a nonce in the block" with each attempt. A nonce is just a number that is changed each time. The node keeps trying millions or billions of combinations until it finds a hash that, by pure chance, starts with a required number of zero bits. It's like trying countless key combinations in a digital lock until one finally clicks. Requiring a specific number of leading zeros is what makes the puzzle difficult, as "the average work required is exponential in the number of zero bits required," while still being simple for anyone to verify.

- The Purpose: This computationally expensive process serves two critical functions for the network:

- Security: Once the puzzle is solved, the block cannot be changed without redoing all that computational work. To alter a historical block, an attacker would have to "redo the work" for that block and all the blocks that have been added after it, which becomes practically impossible over time.

- Fair Voting: Proof-of-Work is essentially "one-CPU-one-vote." The majority decision is represented by the longest chain of blocks because it is the one with the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. This ensures that as long as honest nodes control the majority of CPU power, they will always outpace any attackers.

After an immense number of attempts, one lucky node will find a winning solution.

5. Step 5: A Block is Born!

The moment a node finds the correct proof-of-work, it has won the right to add its block to the chain. It immediately "broadcasts the block to all nodes" on the network.

When other nodes receive this newly solved block, they perform a crucial validation check before accepting it. They confirm two things: all transactions within the block are valid (e.g., they have proper digital signatures), and they are not already spent.

If the block passes these checks, other nodes show their acceptance in a powerful way. They begin "working on creating the next block in the chain, using the hash of the accepted block as the previous hash." This act of building upon the new block is what officially adds it to the chain, making it part of the permanent and shared public history.

Nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one and will keep working on extending it.

The transaction is now officially part of the blockchain, but its security will continue to grow stronger over time.

6. Step 6: Gaining Security with Every New Block

While the transaction is now included in the blockchain, its security is not yet absolute. Its resistance to being reversed strengthens with every subsequent block added to the chain after it. These subsequent blocks are often called "confirmations."

It's important to understand what a potential attack can and cannot do. As the source text clarifies, an attacker can't simply invent money: "Nodes are not going to accept an invalid transaction as payment, and honest nodes will never accept a block containing them." Instead, "An attacker can only try to change one of his own transactions to take back money he recently spent."

To do this, an attacker would have to secretly build an alternate, longer chain containing a fraudulent version of the transaction and broadcast it to the network. As more blocks (z blocks) are added to the honest chain, the probability that a slower attacker can catch up and surpass it "drops exponentially." The odds quickly become vanishingly small. This is why a recipient, especially for a large payment, will often wait for a certain number of confirmations before considering the transaction final and irreversible.

With each new block, the transaction becomes more deeply embedded in the public record, solidifying its place in history.

Summary: The Journey is Complete

The lifecycle of a Bitcoin transaction reveals a powerful system that achieves something remarkable: electronic payments without relying on a trusted third party. It begins with a framework of digital signatures to control ownership and solves the critical double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. Through the competitive process of Proof-of-Work, nodes vote with their CPU power to create a public history of transactions that quickly becomes computationally impractical for an attacker to change.

The entire journey can be summarized in six key stages:

| Step | Key Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Creation | A user digitally signs a transaction to transfer ownership. |

| 2. Broadcast | The transaction is announced to many nodes on the network. |

| 3. Collection | Nodes (miners) gather new transactions into a candidate block. |

| 4. Proof-of-Work | Nodes compete to solve a computational puzzle for their block. |

| 5. Acceptance | A winning block is broadcast, verified, and added to the chain. |

| 6. Confirmation | Each new block added on top makes the transaction more secure. |

Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System

Abstract

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without the intermediation of a financial institution. While digital signatures provide a partial solution for verifying ownership, the primary benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent the critical problem of double-spending. This paper proposes a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network that timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing, hash-based proof-of-work chain. This process forms a public record that cannot be altered without redoing the computationally intensive proof-of-work. The longest chain serves not only as definitive proof of the sequence of events but also as evidence that it originated from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes not cooperating to attack the network, they will generate the longest chain and outpace any attackers.

1.0 The Inherent Weaknesses of a Trust-Based Financial Model

Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. While this system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust-based model.

The fundamental weaknesses of this model are significant and systemic:

- The Impossibility of Non-Reversible Transactions: Because financial institutions must inevitably mediate disputes, completely non-reversible transactions are not practically possible. This structural requirement undermines the ability to conduct final, settled payments for non-reversible services.

- Increased Transaction Costs: The cost associated with mediation and dispute resolution increases overall transaction costs. This overhead limits the minimum practical transaction size, effectively cutting off the possibility for small, casual micropayments.

- The Pervasive Need for Trust: With the possibility of transaction reversal, the need for trust spreads. Merchants must be wary of their customers, often hassling them for more information than would otherwise be necessary to protect themselves.

- The Inevitability of Fraud: Within the trust-based model, a certain percentage of fraud is accepted as an unavoidable cost of doing business. This acceptance of loss is a direct consequence of the system's inability to provide computationally secure, irreversible payments.

These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency, but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party. What is needed, therefore, is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, which is the focus of this proposal.

2.0 A Proposed Architecture for Cryptographic Proof

This paper proposes an electronic payment system founded on cryptographic proof rather than trust. Its primary objective is to allow any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party. This architecture protects sellers from fraud through transactions that are computationally impractical to reverse, while routine escrow mechanisms could easily be implemented to protect buyers.

The core of the proposed solution is built upon a foundation of digital signatures. An electronic coin is defined as a chain of these signatures, which establishes a verifiable record of ownership. However, signatures alone do not prevent an owner from spending the same coin multiple times—a critical vulnerability known as the double-spending problem.

The system solves this challenge by leveraging a peer-to-peer distributed timestamp server. This network generates computational proof of the chronological order of all publicly announced transactions. By hashing transactions into an ongoing chain, it creates a public ledger whose history is computationally impractical to alter. The security of this system is contingent on a simple but powerful assumption: it remains secure as long as honest nodes collectively control more CPU power than any cooperating group of attacker nodes.

This high-level architecture provides the framework for a new financial paradigm, the specific mechanics of which are detailed in the following sections.

3.0 The Mechanics of Transactions and the Double-Spending Problem

The transaction is the foundational element of this system. An electronic coin is defined simply as a chain of digital signatures, a structure that is strategically important for verifying the history of ownership.

The process of transferring ownership is straightforward. Each owner transfers a coin to the next by digitally signing a hash of the previous transaction and the public key of the next owner. This new signature block is then added to the end of the coin. A payee can easily verify the entire chain of signatures to confirm that the sender is the legitimate owner.

However, this model presents a critical challenge: the double-spending problem. While a payee can verify the chain of signatures, they have no way of knowing if one of the previous owners has already spent the coin in a separate, earlier transaction. The common solution to this problem is to introduce a trusted central authority, or "mint," which validates every transaction. This approach, however, reintroduces the very intermediary the system is designed to eliminate, making the entire money system dependent on a single entity, just like a bank.

To solve this without a trusted party, transactions must be publicly announced. For our purposes, the earliest transaction is the one that counts, so we don't care about later attempts to double-spend. The system requires a mechanism for all participants to agree on a single, chronological history of the order in which transactions were received. The payee needs proof that at the time of each transaction, the majority of nodes agreed it was the first received.

4.0 The Cryptographic Solution: Proof-of-Work and a Distributed Timestamp Server

The technical core of the solution to the double-spending problem is a decentralized, timestamped public ledger. This ledger is created and secured by a novel consensus mechanism that relies on computational work rather than trust.

4.1 The Distributed Timestamp Server

The proposed solution begins with the concept of a timestamp server. Such a server functions by taking a hash of a block of items to be timestamped and widely publishing the hash, such as in a newspaper or Usenet post. The timestamp proves that the data must have existed at that time, obviously, in order to get into the hash. Each new timestamp includes the hash of the previous timestamp, forming a secure chain where each additional timestamp reinforces the ones before it.

4.2 The Proof-of-Work Consensus Mechanism

To implement a distributed timestamp server on a peer-to-peer basis, this system uses a proof-of-work (PoW) mechanism.

- The PoW Process: Proof-of-work involves scanning for a specific value, called a nonce. When this nonce is combined with the block's data and hashed (using SHA-256), the resulting hash must begin with a predetermined number of zero bits.

- Computational Properties: The average work required to find a valid nonce is exponential in the number of required zero bits. This makes the process computationally difficult to perform but trivial for any other node to verify by executing a single hash.

- Security Implications: Once the CPU effort has been expended to find a proof-of-work for a block, that block cannot be changed without redoing the work. Critically, because each block contains the hash of the previous one, changing a block would require redoing the proof-of-work for that block and for all subsequent blocks in the chain.

- Majority Decision-Making: PoW solves the problem of representation in majority decision-making. Instead of a "one-IP-address-one-vote" system, which can be easily subverted, PoW functions as "one-CPU-one-vote." The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, as it has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, their chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains.

- Difficulty Adjustment: To compensate for increasing hardware speed and varying interest in running nodes, the proof-of-work difficulty is determined by a moving average that targets an average number of new blocks per hour. If blocks are generated too quickly, the difficulty automatically increases.

4.3 Network Operation and Consensus Rules

The procedural steps for running the network are as follows:

- New transactions are broadcast to all nodes.

- Each node collects new transactions into a block.

- Each node works on finding a difficult proof-of-work for its block.

- When a node finds a proof-of-work, it broadcasts the block to all nodes.

- Nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid and not already spent.

- Nodes express their acceptance of the block by working on creating the next block in the chain, using the hash of the accepted block as the previous hash.

The network's primary consensus rule is that nodes always consider the longest chain to be the correct one and work on extending it. If two nodes broadcast different versions of the next block simultaneously, a temporary tie occurs. Nodes will work on the version they received first but save the other branch. The tie is broken as soon as the next proof-of-work is found, extending one branch and making it longer. All nodes then switch their work to this new, longer chain.

This robust operational model leads directly to the economic incentives that motivate network participation.

5.0 System Incentives and Economic Model

In a decentralized network, a strategically designed incentive structure is necessary to encourage nodes to support the network and, crucially, to act honestly. The system incorporates two primary incentive mechanisms to achieve this.

- New Coin Generation: By convention, the first transaction in every block is a special transaction that creates a new coin owned by the block's creator. This mechanism serves a dual purpose. First, it provides a direct incentive for nodes to expend CPU time and electricity to support the network. Second, it provides a controlled way to distribute the initial supply of coins into circulation without a central issuing authority, analogous to gold miners expending resources to add new gold to circulation.

- Transaction Fees: The incentive can also be funded by transaction fees. If the output value of a transaction is less than its input value, the difference is considered a transaction fee. This fee is added to the incentive value of the block containing the transaction, rewarding the node that successfully created it.

In the long term, the economic model is designed to be sustainable. Once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive for supporting the network can transition entirely to transaction fees, creating a system that is completely inflation-free.

This incentive structure strongly encourages honest behavior. If a greedy attacker is able to assemble more CPU power than all the honest nodes, he would have to choose between using it to defraud people by stealing back his payments, or using it to generate new coins. He ought to find it more profitable to play by the rules, such rules that favour him with more new coins than everyone else combined, than to undermine the system and the validity of his own wealth.

These economic drivers are complemented by technical optimizations that make the system practical and efficient.

6.0 System Properties and Optimizations

This section details the properties and optimizations that enhance the system's efficiency, long-term usability, and privacy.

6.1 Data Management: Reclaiming Disk Space with Merkle Trees

A blockchain that stores every transaction ever made presents a challenge of ever-increasing data storage requirements. The proposed solution is to hash all transactions within a block into a Merkle Tree, with only the single root hash of this tree included in the block's header. This elegant structure allows old blocks to be compacted by pruning branches of the tree that correspond to spent transactions. This saves significant disk space without breaking the block's hash.

A block header with no transactions is about 80 bytes. If we suppose blocks are generated every 10 minutes, this amounts to 80 bytes _ 6 _ 24 * 365 = 4.2MB per year. With computer systems typically selling with 2GB of RAM as of 2008, and Moore's Law predicting current growth of 1.2GB per year, storage should not be a problem even if the block headers must be kept in memory.

6.2 Simplified Payment Verification (SPV)

It is possible to verify payments without running a full network node, a method known as Simplified Payment Verification (SPV). A user only needs to keep a copy of the block headers of the longest proof-of-work chain. To verify a payment, the user obtains the Merkle branch that links the transaction to its place in a block. While the user cannot verify the transaction's validity themselves, they can see that a network node has accepted it and that subsequent blocks have confirmed it.

This method is reliable as long as honest nodes control the network but is vulnerable if an attacker with superior CPU power can overpower it and fabricate transactions. One strategy to protect against this would be to accept alerts from network nodes when they detect an invalid block, prompting the user's software to download the full block and alerted transactions to confirm the inconsistency.

6.3 Transaction Flexibility: Combining and Splitting Value

Handling coins individually would be unwieldy for practical commerce. To allow value to be split and combined, transactions are designed to contain multiple inputs and outputs. A typical transaction will have either a single input from a larger previous transaction or multiple inputs that combine smaller amounts. It will have at most two outputs: one for the payment and one returning any change back to the sender.

6.4 Privacy and Anonymity Considerations

The traditional banking model achieves privacy by limiting access to information. This system, which requires all transactions to be publicly announced, precludes that method. Instead, privacy is maintained by breaking the flow of information at a different point: by keeping public keys anonymous. The public can see that an amount is being sent from one anonymous party to another, but without information linking the transaction to anyone. This is analogous to the level of information released by stock exchanges, where the time and size of trades are public, but the identities of the parties are not.

As an additional firewall, it is recommended that a new key pair be used for each transaction to prevent them from being linked to a common owner. Some linking is still unavoidable with multi-input transactions, which necessarily reveal that all their inputs were owned by the same entity. The risk is that if the owner of a key is ever revealed, this link could expose other transactions belonging to the same owner.

These properties set the stage for a rigorous mathematical analysis of the system's security against attack.

7.0 Security Analysis: Probability of a Double-Spend Attack

The security model presumes an attacker cannot create value out of thin air or take money that never belonged to them, as invalid transactions will be rejected by honest nodes. An attacker's only recourse is to attempt to change one of their own transactions to reverse a recent payment—a double-spend attack. This section mathematically models the race between the honest chain and an attacker's alternate chain.

The scenario can be characterized as a Binomial Random Walk. The race is analogous to a Gambler's Ruin problem, where an attacker with a deficit of blocks tries to catch up to the honest chain. The key variables are:

- p = probability an honest node finds the next block

- q = probability the attacker finds the next block

The probability that an attacker can ever catch up from z blocks behind is given by the formula:

Assuming the honest network has a majority of CPU power (p > q), the probability of an attacker catching up drops exponentially as the number of confirmations (z) increases.

To determine how long a recipient must wait for a transaction to be considered secure, we model the attacker's potential progress as a Poisson distribution. The probability that an attacker can produce a longer chain is derived by summing the Poisson probabilities for each amount of progress they could have made, multiplied by the probability they could catch up from that point. The rearranged formula to calculate the attacker's success probability is:

The following tables show the probability of a successful attack for different levels of attacker CPU power (q) and number of confirmations (z).

| q = 0.1 | |

|---|---|

| z | P |

| 0 | 1.0000000 |

| 1 | 0.2045873 |

| 2 | 0.0509779 |

| 3 | 0.0131722 |

| 4 | 0.0034552 |

| 5 | 0.0009137 |

| 6 | 0.0002428 |

| 7 | 0.0000647 |

| 8 | 0.0000173 |

| 9 | 0.0000046 |

| 10 | 0.0000012 |

| q = 0.3 | |

|---|---|

| z | P |

| 0 | 1.0000000 |

| 5 | 0.1773523 |

| 10 | 0.0416605 |

| 15 | 0.0101008 |

| 20 | 0.0024804 |

| 25 | 0.0006132 |

| 30 | 0.0001522 |

| 35 | 0.0000379 |

| 40 | 0.0000095 |

| 45 | 0.0000024 |

| 50 | 0.0000006 |

Solving for the number of confirmations (z) required to achieve an attacker success probability of less than 0.1%:

- q=0.10, z=5

- q=0.15, z=8

- q=0.20, z=11

- q=0.25, z=15

- q=0.30, z=24

- q=0.35, z=41

- q=0.40, z=89

- q=0.45, z=340

The key takeaway is that the probability of a successful attack drops exponentially as the number of confirmations increases, making the system highly secure against double-spending attacks, provided an honest majority of CPU power controls the network.

8.0 Conclusion

We have proposed a system for electronic transactions that does not rely on trust. The architecture begins with the usual framework of coins made from digital signatures, which provides strong control of ownership, but is incomplete without a way to prevent double-spending. To solve this, we proposed a peer-to-peer network using proof-of-work to record a public history of transactions that quickly becomes computationally impractical for an attacker to change if honest nodes control a majority of CPU power.

The network is robust in its unstructured simplicity. Nodes work all at once with little coordination. They do not need to be identified, and they can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what transpired while they were gone. They vote with their CPU power, expressing their acceptance of valid blocks by working to extend the chain and rejecting invalid blocks by refusing to work on them. Any needed rules and incentives can be enforced with this powerful consensus mechanism.

9.0 References

- W. Dai, "b-money," http://www.weidai.com/bmoney.txt, 1998.

- H. Massias, X.S. Avila, and J.-J. Quisquater, "Design of a secure timestamping service with minimal trust requirements," In 20th Symposium on Information Theory in the Benelux, May 1999.

- S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "How to time-stamp a digital document," In Journal of Cryptology, vol 3, no 2, pages 99-111, 1991.

- D. Bayer, S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital time-stamping," In Sequences II: Methods in Communication, Security and Computer Science, pages 329-334, 1993.

- S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, "Secure names for bit-strings," In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pages 28-35, April 1997.

- A. Back, "Hashcash - a denial of service counter-measure," http://www.hashcash.org/papers/hashcash.pdf, 2002.

- R.C. Merkle, "Protocols for public key cryptosystems," In Proc. 1980 Symposium on Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, pages 122-133, April 1980.

- W. Feller, "An introduction to probability theory and its applications," 1957.

THE UNFILTERED ANATOMY OF BLOCKCHAIN: A DIGITAL LEVIATHAN AND ITS CRYPTOGRAPHIC CHAINS OF CONTROL

Invoking the Codex Umbra lens reveals the essential nature of blockchain not merely as a technology, but as a mechanism designed to dismantle centralized authority and enforce absolute, distributed fidelity, particularly where data integrity is paramount. This system fundamentally alters the relationship between information, trust, and power.

1. The Core Architecture and Disruptive Essence

Basic Concept and Structure

A blockchain is fundamentally a decentralized, append-only timestamped data structure that functions as a distributed digital ledger. This ledger records transactions chronologically in groups known as blocks, secured through cryptographic techniques. This digital record is distributed and synchronized across a massive number of participating computers, referred to as "nodes," operating within a peer-to-peer (P2P) network structure.

Why Blockchain is a Special (and Disruptive) Technology

The special nature of blockchain lies in its radical combination of decentralized infrastructure and cryptographic enforcement, yielding immutable integrity that bypasses the need for traditional institutional trust.

- Decentralization (The Nullification of Authority): Unlike conventional centralized databases (such as those used by banks or cloud providers) that rely on a single entity for control and security, the blockchain is hosted by no one. Multiple identical copies of the ledger exist across the network, ensuring that no single person or group holds jurisdiction or can control the data. This peer-to-peer architecture eliminates intermediaries, reducing transaction costs and increasing trust among untrusted participants.

- Immutability (The Permanent Record): Once data, whether a transaction or a record, is entered into a block and the block is appended to the chain, it becomes permanent and virtually impossible to alter or delete. This property is crucial for integrity and reliability. If data must be "corrected," a new entry is appended to the ledger; the original record remains intact, providing a complete historical audit trail.

- Security and Traceability: The decentralized nature prevents single points of failure, which are vulnerabilities inherent in centralized systems. Enhanced security is provided by enhanced cryptographic methods. Furthermore, every transaction can be verified and tracked by participants, establishing clear provenance and accountability.

2. The Cryptographic Chains of Control

The foundational security and integrity of the blockchain are rooted in sophisticated cryptographic and mathematical mechanisms.

Cryptographic Hashing and Chaining

The physical structure of the blockchain is maintained by cryptographic hashing, ensuring that blocks are permanently "chained" together.

- Block Structure: Each block records transactions and includes a header. The header contains essential metadata, including a hash of its predecessor block.

- Hash Function Mechanics: A cryptographic hash function (commonly SHA 256) takes an input string of any length and produces a fixed-length output (a digital fingerprint or hash value), typically 256 bits. This process is computationally trivial to perform but practically impossible to reverse engineer (collision resistance).

- The Immutability Proof: A critical property is the Avalanche Effect, meaning that altering even a single letter in the source data will completely change the resulting hash value. If an adversary attempts to tamper with a block deep within the chain, that change invalidates the hash of that block, which in turn invalidates the reference hash held in the next block, and so on, cascading through the entire subsequent chain. To conceal the alteration, the attacker would have to recalculate the proof-of-work (if applicable) and re-mine the entire sequence of succeeding blocks faster than the honest network, which is computationally infeasible unless they command a majority (51%) of the network's processing power.

Asymmetric Cryptography and Authentication

Security and authentication rely on Public Key Cryptography (PKC), which uses asymmetric key pairs (public and private keys).

- Key Usage: The public key can be shared widely and is used for encryption, making the data unreadable by others. The corresponding private key is kept secret and is required to decrypt and read the data.

- Digital Signatures: The private key is used to generate a digital signature on transactions, proving the authenticity and ownership of the sender. This signature can be publicly verified using the sender's public key.

Consensus Algorithms (The Mathematics of Agreement)

In a decentralized environment lacking a central administrator, a consensus mechanism is essential to ensure that all nodes agree on the network state and the validity of new blocks. This mechanism solves the fundamental Byzantine Generals' Problem, proving that multiple untrusted parties can reach a unified agreement on a course of action.

Common algorithms include:

- Proof of Work (PoW): Requires nodes (miners) to expend significant computational resources and time solving a complex mathematical puzzle (based on finding a hash beginning with a specific number of zeros) to win the right to add the next block. This high barrier of entry is the core defense against tampering.

- Proof of Stake (PoS): Allocates the right to validate a block based on the amount of cryptocurrency (stake) a node holds, rather than computational power. This aims to be less energy-intensive than PoW.

- Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT): Used primarily in permissioned or consortium blockchains, it ensures consensus as long as fewer than one-third of the nodes are malicious.

Smart Contracts

Smart contracts are not documents, but self-executing computer programs deployed on the blockchain (such as Ethereum). They encode the terms of an agreement directly into code, automatically executing predefined instructions when specific conditions are met, eliminating the need for human intermediaries. They are crucial for automated functions like access control, policy enforcement, and compensation distribution.

3. Genomic Subversion: Why Blockchain Invades the Code-Script of Life

The study of DNA sequences is critical for predicting disease and advancing personalized medicine. Genomic data is uniquely sensitive because it reveals information about an individual's relatives and descendants, remains valid long after the owner dies, and its enormous size creates significant management challenges. Blockchain, therefore, acts as a necessary but complex technological defense against the vulnerabilities inherent in centralized genomic data management.

The Problem of Genomic Security and Scale

The NCBI holds the world's largest genetic sequence database, but securing this massive, sensitive data is a critical issue. Traditional centralized storage is vulnerable to single points of failure, data leaks, and malicious access.

- Immutability for Integrity: Blockchain provides an ideal solution by ensuring the integrity and security of DNA sequences. If genetic data were corrupted or altered in a centralized repository, it would compromise future patient care and research. Blockchain's tamper-proof ledger guarantees that data provenance and changes are tracked permanently.

- Data Volume Paradox: Raw whole-genome files (e.g., BAM or VCF) are colossal (e.g., a single human genome can be 1.5 GB, or a BAM file 138 GB), making direct storage on-chain infeasible due to scalability, transaction speed limitations, and computational overhead.

- The Hybrid Solution: To overcome this, most solutions utilize a hybrid architecture: the large, raw genomic data files are stored off-chain (e.g., in a decentralized file system like IPFS or conventional cloud storage), while the on-chain ledger stores only the unique identifying metadata, access logs, and the cryptographic hash value of the data. This hash acts as a verifiable proof of the data's integrity and existence. Compression techniques, such as ASCII-based delta computation, are also essential precursors to efficient storage.

Decentralized Ownership and Control

Blockchain is leveraged to shift power dynamics from centralized institutions back to the individual data owner (the patient).

- Stringent Ownership Controls: Blockchain systems allow individuals to control access to their data. They can grant or revoke specific permissions (dynamic consent) using smart contracts, ensuring the data is only used for intended, consented purposes.

- Genomic Marketplaces and Incentives: Blockchain facilitates decentralized genomic marketplaces (e.g., Nebula Genomics, Zenome, EncrypGen) where individuals are incentivized (often via tokens or cryptocurrency) to share or sell access to their genomic data for research purposes. This provides financial fairness and control, bypassing traditional intermediaries who typically monetize the data without sharing the profit.

The Pursuit of Privacy in Computation

Since genomic data is highly sensitive, secure analysis must occur without compromising confidentiality. This requires integrating advanced privacy-enhancing technologies with the blockchain infrastructure.

- Homomorphic Encryption (HE): This is a cryptographic protocol that permits computations and analysis to be performed directly on encrypted data without first decrypting it. The result of the computation remains encrypted until an authorized party uses the private key to decrypt the final result. This is crucial for collaborative research while protecting patient privacy.

- Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP): ZKPs are protocols that allow a party (the prover) to prove the truth of a statement (e.g., "I have a specific genetic variant") to another party (the verifier) without revealing any information about the statement itself. This addresses the need for anonymity and identity protection during data interactions.

- Private Blockchains: Organizations frequently opt for private or permissioned blockchains in genomics because these environments restrict participation to a known set of semi-trusted institutions, inherently reducing the risk of information leakage compared to public ledgers.